“Donoher means Dayton basketball, and Dayton basketball means Don Donoher,” read the subhead 40 years ago.

Nuhn died in 2024 at 77. His legacy lives on in microfilm, in newspapers saved by the Flyer Faithful and on the internet. Every edition of the Dayton Daily News, going back to 1882, is searchable on Newspapers.com.

That’s how I found another DDN Magazine piece by Nuhn. On March 8, 1987, he wrote about the 20th anniversary of the 1967 Dayton Flyers, who advanced further in the NCAA tournament than any UD before or since, reaching the national championship game.

“If you care the least bit about University of Dayton basketball,” wrote Dayton Daily News editor Ralph Morrow, who introduced the story in the magazine, “you’ll revel in Gary Nuhn’s story about the team’s run to the national championship game in 1967.

“In his story that begins on Page 12, he talks with the players who accomplished the impossible. Besides the players, there were a lot of other people who were present in Louisville as the Flyers completed its run of upsets by knocking off North Carolina before losing to everyone’s No. 1, UCLA.”

I thought the story was worth bringing back to life in print and on DaytonDailyNews.com. Here it is.

The ‘67 Flyers: The Team Looks Back on the Tournament that Ignited a City

It was 20 years ago this month.

The Beatles were experimenting with hallucinogens. A flicker of a girl with a strange name, Twiggy, was arriving in New York for the first time. There was a slush fund scandal at the University of Illinois that nearly turned the Big Ten into the Big Nine.

Gary Nolan was a rookie phenom with the Reds. Sandra Dee and Bobby Darin were getting divorced. We were sending our children to die in Vietnam.

And a basketball team from Dayton was finding gold coins under every rock.

It seems less than 20 years. The good times, the bad times, they always seem as if we can reach back and touch them at will.

It’s the indifferent times that mock us.

But this was a good time. It began on a Saturday right in Lexington, Ky., and ended two weeks later about 90 miles down the road in Louisville. They were 14 days that captivated and united a city, and set it to boiling.

Bobby Joe Hooper made a shot at one end.

Donnie May made a baker’s dozen at the other. And Dayton — the city, the area — got giddy in between.

You didn’t go anywhere in those two weeks — you didn’t buy groceries or turn on your radio or stop for gas — but what the Dayton Flyers weren’t Subject One.

That UCLA put a sledgehammer to the glee is almost a postscript; because you couldn’t take away those magical, mystical two weeks of mirth with all the sledgehammers in Los Angeles.

Fourteen Flyers lived the glory, along with two managers and two coaches.

John Samanich, a substitute forward, may have said it best: “We were just a bunch of kids who wouldn’t take no for an answer.”

The 20 years since have been kind to some, unkind to others. There have been dozens of job switches as men searched for their calling. There have been good marriages and bad.

As close as the team was, few players see each other anymore.

Most look back and talk of that frozen moment with joy in their voices.

But not all.

Glinder Torain, a strapping 6-foot-7 center/forward, long ago estranged himself from the university. He is in Belgium.

John Rohm, a backup center, lives in Indiana. Reached by telephone and told a story was being done about the ’66-67 Flyers, Rohm said, “That’s a dirty word. Go to hell.” and hung up.

Rudy Waterman, a make-something-happen guard, left UD embittered by perceived racism, but, unlike Torain, he eventually reconciled with coach Don Donoher. Then, however, Waterman suffered personal problems he couldn’t handle. He shot himself to death in 1981.

This is the story of those Flyers. This is how it was and how they remember it being.

It’s a tossup as to which is more important.

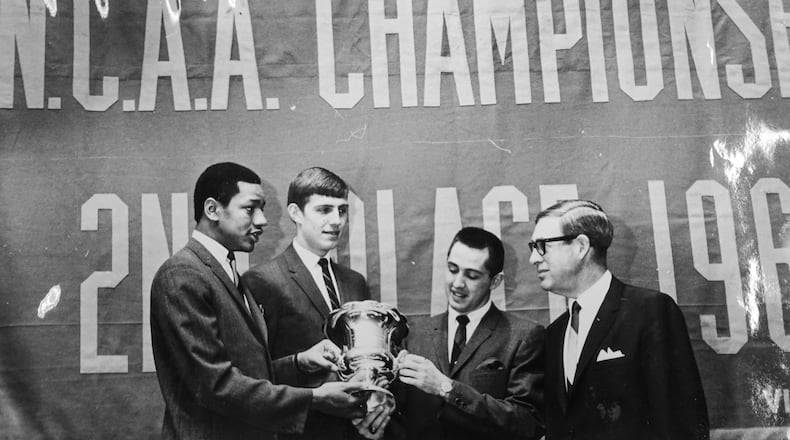

Credit: HANDOUT

Credit: HANDOUT

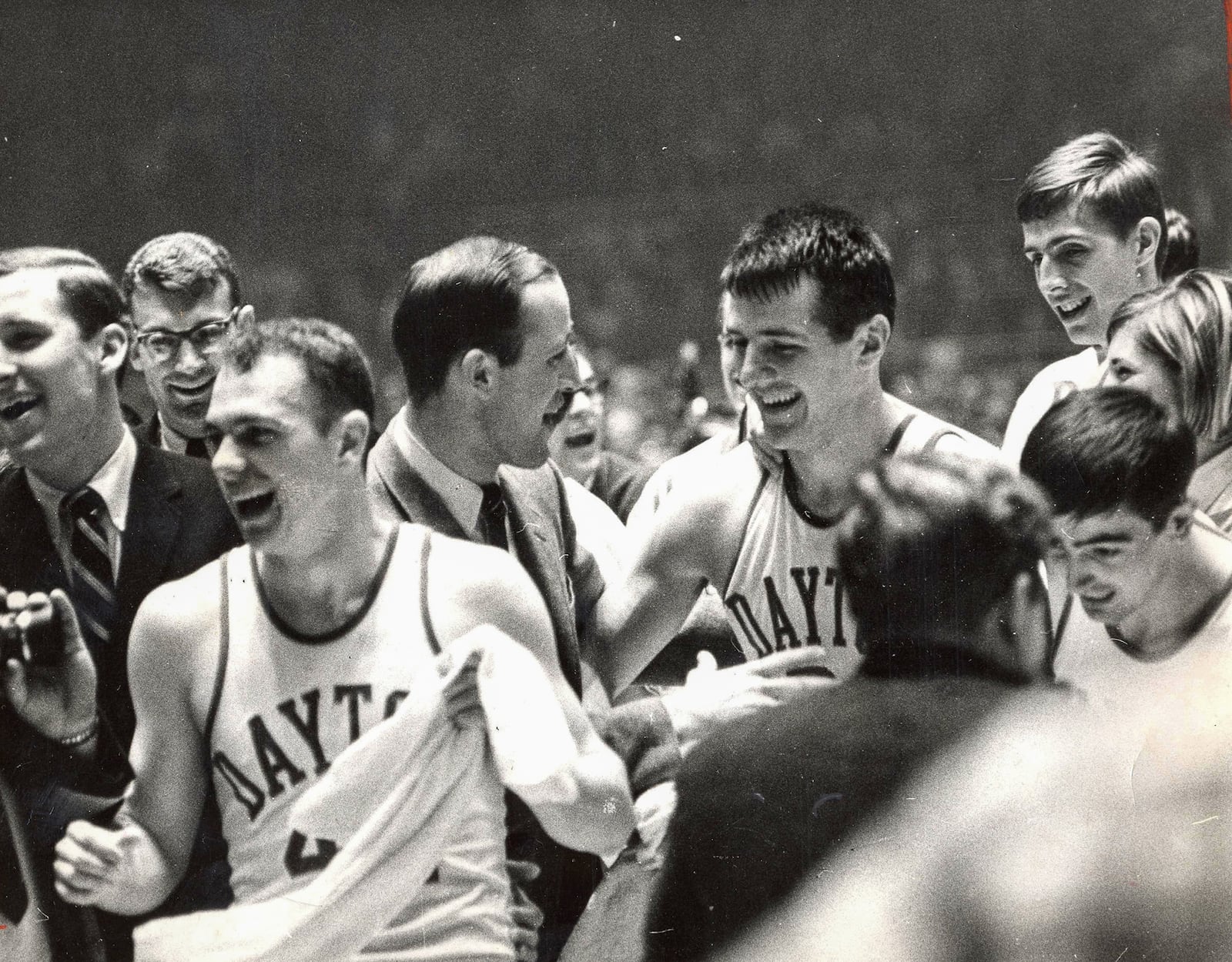

Credit: TIMOTHY BOONE

Credit: TIMOTHY BOONE

Hooper’s shot nothing but net

Tournament bids came early in those days.

The Flyers’ bid came a week before the season ended when they were 21-4. They lost their final regular-season game to DePaul, which may have been a blessing. Any complacency that might have creeped in was erased with that loss.

The first round was in Lexington against Western Kentucky, 22-3 and ranked No. 6 in the country. But Western had a problem. Leading scorer Clem Haskins had broken his wrist in early February. He had come back for the Hilltoppers’ final two games with his wrist heavily taped. He had done well in the first, but went 0 for 7 in the second.

Donoher recalls that Haskins “mishandled the ball a lot, especially in the first half.” At halftime, the Toppers were 10 up. Waterman led a second-half rally, scoring nine points in a row, and the Flyers took the lead. But with a chance to win it, Waterman’s shot with three seconds to play rimmed in and out as did Torain’s tip attempt.

In overtime. Western tied it 67-67 with 36 seconds left. Dayton milked the clock to 13 seconds, then called time.

Assistant Coach Chuck Grigsby tells what happened in the huddle: “Hooper came in and said, ‘Gimme the ball and get out of my way.’”

Hooper laughs at that version. “My memory of it,” he says, “is that I had played so bad all night (he had just five points in regulation), I begged them to give me the ball so I could have a chance to make up for it. I said it pretty close to the end of the timeout, and I think it surprised them (the coaches) so much, they just said, ‘OK.’”

Hooper passed the ball to Gene Klaus off the left sideline and got it back immediately. He then dribbled across the top of the key to the right side. stopped and put one up from 20 feet.

“It was about 25 feet,” says Jim Wannemacher.

“As you get older,” says Hooper, “it gets farther.”

One thing everyone agrees about.

“It ripped the net perfectly,” says Wannemacher.

It did so with four seconds remaining. Western had no more timeouts.

It was over.

UD’s bench and fans exploded.

“I went crazy.” says Hooper.

“I went crazy,” says Rich Fox.

“Everybody went crazy,” says Donoher.

Naturally.

“I was under the basket,” says May, “and seeing it go through was such a relief. There was no thought of the next game or the next round, anything. It was just relief.”

“I came charging off the bench as the shot went through,” says Ned Sharpenter, “and Bobby jumped right up in my face and bear-hugged me.”

Something else has stayed with Hooper all these years. “My mom and dad were there,” he says. “I remember fighting my way through the mob to find them. I hugged Mom. And Dad, being an old coach, he just shook my hand and said, ‘Not bad.’”

Long afterward, as the weary Flyers boarded their bus for the ride home, manager Dave Borchers remembers a remarkable thing.

“Haskins was out there by our bus with his hand in the cast,” Borchers says, “shaking hands with us as we got on and telling us, ‘Good luck.’”

You want a new definition of class? Clem Haskins. March 11, 1967.

Obrovac faces a Tennessee giant

The victory earned the Flyers a trip to Evanston, Ill., for the Mideast Regional.

There, Tennessee, 21-5, the Southeastern Conference champion and ranked No. 8 in the country, waited.

Tennessee’s center was Tom Boerwinkle, a 7-footer and a 300-pounder.

“The biggest human being I had ever seen up until then,” says Dan Sadlier.

But Sadlier didn’t have to face him. Dan Obrovac did.

“I ran into him a couple of times,” says Obrovac, “and I came to a dead stop.”

Tennessee also had Ron Widby, a 22.2 scorer and all-around athlete who eventually became a punter in the NFL.

That was Sadlier’s man.

“I think he got 52 a couple of weeks before,” Sadlier says.

Tennessee, led by former Wittenberg coach Ray Mears, was heavily favored, not only to beat UD, but to make it to the Final Four. “Tennessee Waltz,” Sharpenter remembers the headline in Sports Illustrated.

The Vols set up in a 1-3-1 zone that collapsed around May, Sadlier and Obrovac or Torain and dared the guards to shoot.

Hooper and Klaus took the dare.

“I was mad at coach Mears,” said Hooper, “because during the week he had said, ‘We’ll play our zone because Dayton’s guards can’t shoot.’”

If Mears said that, he never said it to a Dayton writer. No quote like that appeared in either Dayton paper.

But whether he said it or not isn’t important. That Hooper and Klaus thought he said it was.

The two Flyer guards sent guided missiles over the Tennessee zone. Klaus was 5 of 7 from long range. Hooper was 6 of 7.

UD built an 11-point halftime lead, but the Vols erased it in the first five minutes of the second half.

The rest of the game was a slowdown. Mears held the ball because Boerwinkle had four fouls. Donoher held the ball to try to protect UD’s slim lead.

There were only two shots taken from 7:18 through 0:15, both by Tennessee. Hooper’s free throw with 24 seconds remaining put UD up 51-50.

With eight seconds to play, Widby missed a 15-foot jumper that Sadlier rebounded. He was fouled and made a free throw to make it 52-50. Tennessee then threw away the in-bounds pass, and Torain added a free throw with five seconds to go to make it 53-50. Tennessee scored at the buzzer to make the final 53-52.

From the Department of Incredible Statistics: UD was called for just one foul in the second half.

“It was the best game Bobby and I had,” says Klaus. “We were a team that just hung in and hung in and hung in until something good happened.”

Overtime, but a fan steals the show

Amazingly, this was a regional final. It went to overtime.

Yet few of the players have any recollection of the game.

They all remember a Virginia Tech guard named Glen Combs. He hit five consecutive jump shots starting at about 25 feet and progressively working his way back to 30.

But the other details are foggy at best.

That Tech was 20-6, like UD unranked, and had beaten Indiana 79-70 the night before. All that, as May says, “is a blur.”

Borchers remembers the definitive scene, the one many fans might remember. It was of UD student Jack Hoeft trying to cut down one of the nets after the game. The McGaw Hall maintenance people saw Hoeft hanging onto the rim with a knife in hand and pushed the button that raised the backboard and basket into the rafters.

Hoeft, however, refused to let go. Pretty soon, he was 30 feet up, dangling like a circus act. Finally, after a minute that seemed like 15, the backboard was lowered, and Hoeft walked away with his prize.

But that was postgame. What about midgame?

“Rudy Waterman made some plays,” remembers Sadlier.

“The only reason we beat ‘em,” says Sharpenter, “is we had Donnie May.”

That’s Donoher’s memory also. “I remember that kid Combs finally missed one,” Donoher says, “and then we just started going with May, riding him. We’d run our pattern, post him deep and go right to him.”

They rode Donnie May right to the finals.

Memories are selective sometimes.

Yes, Combs made five shots in a row early in the second half to stake the Gobblers to a 10-point lead, but he also missed 16 shots on the night (he was 7 of 23), including the last seven he took.

May had 28 points and 16 rebounds, moving Tech Coach Howie Shannon to call May the best player he’d seen all year.

And then there was the coaching contribution.

With the score tied in regulation and 30 seconds left, Tech’s Ron Perry was dribbling at midcourt, waiting for a last-second shot.

Sadlier closed in on Perry, but Perry didn’t move.

Donoher and Grigsby leaped off the bench, each with both thumbs in the air, asking for a five-second call and a jump ball. As if on cue, official Mike Di Tomasso made the call.

Sadlier controlled the tip, and although Hooper missed a shot with one seconds to play, the jump-ball call had cost Tech a chance to win it. In OT. Waterman made the free throw that put UD up for good, then made a great feed to May for a bucket. In the final 33 seconds, Torain and Hooper hit two free throws each, and it was off to see the wizard, the wonderful Wizard of Westwood.

“The thing I remember,” says May, “is the expression on (athletic director) Tom Frericks’ face as we walked off the floor. I’ve never seen such a delighted face. I realized from reading that face what we’d accomplished.”

The scorebook tells a story, too. It shows something that could never happen today, an era when coaches choreograph almost every footstep of every play in any close game: In 45 minutes, through a heart-pounding finish to regulation, plus an overtime, Donoher used just one timeout.

Asked about it now, the coach draws a blank. “I don’t know what the deal was,” he says.

One more night to remember for the scourge of the south

Before the Flyers could face the Wizard, UCLA coach John Wooden, they had to play North Carolina.

Carolina was 26-4 and No. 4 in the country. And that Virginia Tech team Dayton had just struggled to beat? Carolina had mugged Tech earlier in the season 110-78.

Carolina was a heavy favorite, and not only with the bookies. “Frankly,” says Donoher, “as I looked at them on tape, I thought we’d get drilled.”

But the team from Ohio had one more ambush in it, one more Night to Remember.

Or, as Grigsby said, “Sometimes you’re so close to your kids, you don’t see their strengths. You can’t sell short the will to win.”

It started slowly. The Tar Heels went up 9-2.

This is what UD’s coaches feared the most — an early Heel lead followed by a quick shift into coach Dean Smith’s relatively new four-corner formation and a game-long chase by the Flyers.

But Smith didn’t go four-corner. He elected to keep playing.

And May began to purr. He hit a couple of shots.

He hit a couple more. And a couple more. And so on and so forth into the night.

May I, Mother? Yes, you May.

It is funny to listen to the Flyers recall that splendid sequence when Donnie May filled it up at Freedom Hall.

“Well, let’s see.” says one. “It was 7 or 8 at least.

“Eleven, I believe,” says another.

“It was 14 or 15,” says another.

“I think he hit 16 straight,” says Sadlier.

Told it was 13, not 16, Sadlier doesn’t skip a beat.

“Well,” he says, “Donnie always tells me it was 16.”

He is kidding, of course. If anything, May probably told him it was 10.

But it was 13 in a row, and Carolina reeled around the ring, then went down for the count.

“The shots just started falling,” says May. “I didn’t even know I was on a string. It’s hard to describe how my mind worked in a game. I only thought of that possession; of that play. It was always so basic. ‘Get the ball in the hole. Get the rebound. I never thought ahead or behind. After the game, some writer asked me about it. I had no idea.”

It wasn’t all May, even with his 34 points and 15 boards.

Hooper and Klaus handled Carolina’s feared run-and-jump trap press like professional hunters strolling through a zoo.

“The coaches had it scouted perfectly,” says Hooper. “They told us to keep our dribble and reverse the ball and it would open right up. That’s just what happened.”

“I think,” says Klaus, who scored 15, “that may have been our perfect game.”

Sadlier put a muzzle on NC’s All-America forward Larry Miller. Averaging 22.5. Miller scored 13.

The final was 76-62.

“After it was over,” says May, “the Carolina players probably said, ‘I can’t believe this team beat us.’”

Believe it or not, UD had beaten Western Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia Tech and North Carolina. A Carolina paper proclaimed the Flyers, “The Scourge of the South.”

Alas, UCLA was from the West.

Dayton meets the big man and is left with no excuses

“And then,” says Dave Inderrieden, “we met the big man.”

Yes, they did. Sophomore Lew Alcindor (now Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) was listed at 7-foot-1 3/8 then. Now we know he was actually 7-4.

The managers were duly impressed.

Borchers: “I saw him in the lobby before the game. He sank down into a chair, and all you could see were these knees.”

Manager Joe Emmrich: “He walked past our bench before the game. And he was the biggest s.o.b. I ever saw. I thought to myself, “God, he’s 7-foot-13!’”

The Flyers shared the Kentucky Hotel with the Bruins.

“We saw a lot of their cheerleaders,” says Sharpenter, “and it was a whole lot better than running into their team.”

In those days, there wasn’t a day off between the semis and the finals, as today. It was Friday night-Saturday night: good luck in preparations.

Still, none of the Flyers use that as an excuse for what happened.

Neither do they use the excuse of the hubbub that surrounded them at the hotel as Flyer fans celebrated big-time.

“We could have been in a library and it wouldn’t have made any difference,” says Donoher.

Back then, however, he had changed his mind on one thing. Even he believed. “I was beginning to feel we could play with anybody, including them,” he says.

They couldn’t.

Obrovac took a peek at UCLA’s end during warmups.

“Alcindor was down there with a bunch of photographers around him,” Obrovac says. “He jumped up and touched the ball on the upper corner of the backboard, and then casually dropped the ball through the rim. I thought to myself, ‘Holy (expletive deleted).’”

Alcindor didn’t take warmups too seriously. “I looked down once,” Inderrieden says, “and he was sitting on the bench with his arms and legs folded.”

Obrovac won the opening tip.

“But then,” says Obrovac, “I took the first shot from the top of the key, one of their guys snarled up the rebound and they scored 12 or 14 straight.” (About 10 years later, Obrovac met Jabbar in the Chicago airport. Jabbar recognized him. He told a man who was with him, “This is Obrovac. He got the jump on me.”

(“Yeah,” his friend said, “but you can count the times you got the jump on one hand.”)

Donoher says the then-Alcindor had terrible problems getting his timing down on jump balls.

The other 39 minutes and 59 seconds, however, Lewie did OK.

And the Bruins, who had ripped Houston in the semis, 73-58, did, also in finishing a perfect 30-0.

“Their guards (Lucius Allen and Mike Warren) were like lightning.” says Sharpenter. “When they wanted the ball, they just took it.”

Says Emmrich, “Allen and Warren were so quick, it was like there were four of ‘em.” The other UCLA starters were forwards Lynn Shackleford (for offense) and Ken Heitz (for defense). UD missed its first eight shots and 16 of its first 18.

“I was horrible,” says May. “I totally choked.”

It was quickly 20-4, UCLA.

Says Sadlier, understating just a bit: “Things didn’t work out real well.”

Wooden became a hero to the Flyers. He began substituting early in the second half. Still up by 29 with four minutes to go, he sent in the far end of the bench and let Dayton chop the final score to 79-64.

“Wooden was a man of tremendous class,” says Hooper. “It ended up 15, but it probably could have been 35.”

Says Sharpenter, “If he’d wanted to set a precedent for blowouts, he could have.

Alcindor finished with 20 points, 18 rebounds.

May, after a poor start, had 21 points, 17 boards.

Grigsby recalls, “On the way home one of our fans said Alcindor didn’t impress him. “Yeah,’ I said, ‘All he did was take us out of our offense and take us out of our defense. Other than that, he didn’t impress us much.’”

Hard-working kids go home to glory

Dayton flew home the next day. Easter Sunday.

“People lined up all the way from the airport to downtown to greet us,” says Heckman.

They were in yards and in trees. They honked car horns and waved pennants.

The caravan finished at UD Fieldhouse, where the politicians did their thing, and the players were greeted as conquering heroes.

Three days later, in an amazing overreaction to Alcindor, the rules committee outlawed the dunk.

It stayed illegal until 1976.

For the next two weeks, the team went from one restaurant to another as the town’s restaurateurs feted them.

“I partied for 30 straight days,” says Fox. “When I tell people about that restaurant deal, nobody believes me.”

Then, the Flyers slowly returned to normalcy. Very slowly.

The NCAA sent a check for slightly more than $33,000. Today, if you make the Final Four, it’s worth more than a million bucks.

How had it happened?

Samanich: “When you look at us individually, other than May, we were just a bunch of kids who worked hard.”

What did it all mean?

Hooper: “What we’d proved is a bunch of little country kids could stay with the kids from the big city.”

It also meant something else.

Obrovac: “I couldn’t buy a beer for four years afterward.”

And the beat goes on.

Obrovac again: “People still come up to me and say, ‘I remember when ...’”

About the Author